-40%

Original HAND SIGNED Jewish ART LITHOGRAPH Polish SHTETL Judaica STETL Holocaust

$ 60.72

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

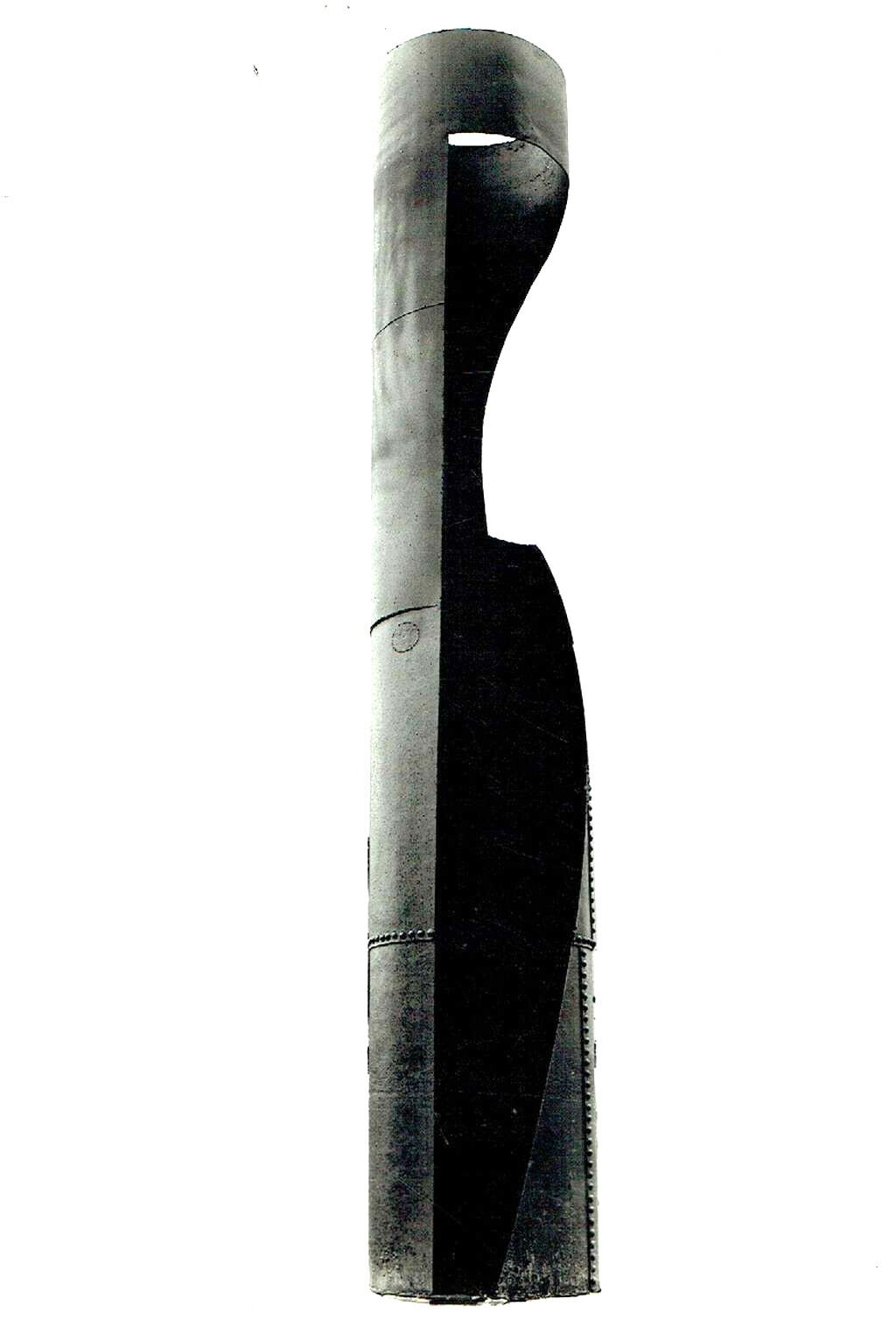

The HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR Tel Aviv POLISH-ISRAELI ARTIST Moshe BERNSTEIN has dedicated his whole JEWISH - POLISH ART to the DESTRUCTED Jewish-Yiddish SHTETL ( Stetl ) Sights, Types, Images, Famillies , Alleys and Streets . IMAGES which were perished forever after the total destruction in the HOLOCAUST. This is a magnificent example of his UNIQUE JEWISH ART. 50 years ago , In 1971, He painted this image of an old SHTETL MAN watching his old POCKET WATCH.

Being familliar with the artist main themes , Being the JEWISH LIFE which were destructed and demolished in the HOLOCAUST , This IMAGE is a mourning about the

JEWISH LIFE and TYPES which were destructed and demolished in the HOLOCAUST .

BERNSTEIN has personaly named this piece in Hebrew , With pencil by hand "UNCLE PINIEH" and dedicated this copy in Hebrew to his friend Avraham Tahor

.The LARGE LITHOGRAPH is numbered 87/150 and dated 1971. Heavy lithograph paper. Size around 26" x 19" .

Very good condition.

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) Will be sent inside a protective tube .

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal

& All credit cards

.

SHIPPMENT

:

Shipp worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25

.

Will be sent inside a protective rigid tube

.

Will be sent around 5 days after payment .

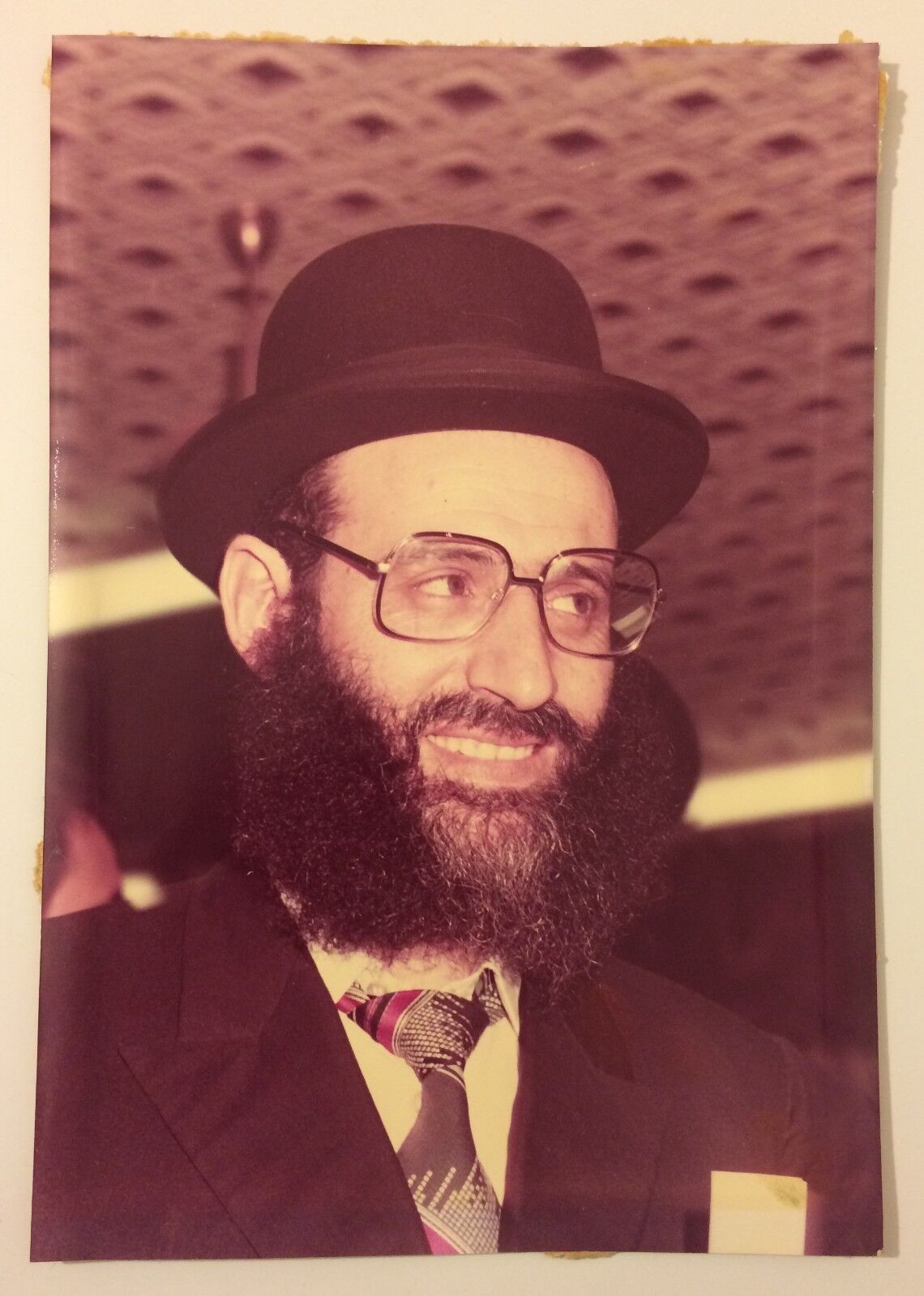

Moshe Bernstein, Israeli painter, born in Poland, 1920-2006 Moshe Bernstein was born in Bereza, Poland. He graduated from Vilna Academy of Art in 1939. His family was wiped out in the Holocaust, but he survived the war and remained in Russia until 1947, when he attempted to immigrate illegally to the Land of Israel with Aliyah Bet. He ended up in a detention camp in Cyprus, where he remained until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. He fought in the War of Independence. Bernstein's art focused on his memories from the shtetl. In 1999, the Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust awarded him a prize for his "documentation of a vanished world." He also illustrated volumes of Yiddish poetry and other books. Education 1935-1939 Art Academy of Vilna 1974 sculpture under Zeev Ben Zvi in Cyprus Awards And Prizes 1980 City Medal, Tel Aviv Moshe Bernstein, Painter and Illustrator, Dies at 86 Born in Poland in 1920, Bernstein was a well-known figure in Tel Aviv's old bohemian circles and the art world. Dana Gilerman and Haaretz Correspondent Dec 11, 2006 12:00 AM 0 comments Zen Subscribe now Share share on facebook Tweet send via email reddit stumbleupon The painter Moshe Bernstein, a well-known figure in Tel Aviv's old bohemian circles and in the world of art, died late last week. He was 86. Born in Poland in 1920, Bernstein completed his art studies in the Academy of Vilna in 1939. His family was wiped out in the Holocaust, but he survived the war and lived in Russia until 1947, when he immigrated to Palestine as part of the "illegal immigration" (aliyah bet). He was caught and spent time in a detention camp in Cyprus. Bernstein's artistic path in Israel recalls that of other painters who reflected their memories of small Jewish Diaspora towns, or shtetls. At a certain stage, these artists were rejected by the local art scene. In the 1950s, '60s and '70s, the subject aroused public interest and recognition. In 1948, Bernstein participated in a group exhibit in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and in 1949 in a group exhibit at Artists' House (then known as the Artists' Pavilion). In 1954, he participated in another exhibition - of young artists - in the Tel Aviv Museum. In 1962, he had a solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum, another in 1967 at the Haifa Museum, and a retrospective in 1973 in the Ein Harod Museum of Art. Interspersed among these events were shows at the Katz and Chemerinsky Galleries in Tel Aviv. A Bernstein exhibit, which included paintings of the shtetl, was shown in 1998 at the international theater festival in Parma, Italy. In 1999, he was awarded a prize by the Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust, for his "documentation of the world that vanished at the beginning of his career." His paintings appeared on the walls of the defunct Kassit cafe in Tel Aviv, and in the Kiton restaurant - "places in which he ate and gave paintings," says gallery owner Zaki Rosenfeld, whose father, Eliezer Rosenfeld, worked with Bernstein. Bernstein's paintings always touched on memories of the Jewish town he was forced to leave at a young age. They were a constant reminder of the destruction of European Jewry, but also expressed great yearning. Bernstein wrote in the catalogue of the 1973 exhibition in Ein Harod: "In this exhibition, I once again bring you the experiences and dreams of my longed-for past, because for me it is an enchanted garden which I walk as if intoxicated by its fragrances and its beauty, and from which I draw the inspiration for my work." "Moshe was one of those young artists who gave expression to a different kind of experience in that period," says Galia Bar-Or, curator and director of the Ein Harod Museum of Art. "He is perceived as the kind of Jewish artist that gives sentimental expression to the memory of a Jewish culture that is gone forever. He also illustrated books of Yiddish poetry. He did the typography by hand, in black ink; and in his decorations around the sides there appeared that same figure of a Jewish girl, with a black braid and big eyes, and the houses of the town." Keep updated: Sign up to our newsletter Email* Sign up At a certain stage he began to concentrate increasingly on graphic art. Among others, he illustrated Israel Ch. Biletzky's book, "A Jewish Shtetl," which was published in 1986. "My father, who also came from the shtetl, worked with him for years, and loved his work," says Zaki Rosenfeld about Bernstein. "He belonged to that same vanishing group of artists who represented and preserved the cultural fabric from which they themselves came. When I turned the gallery into a gallery of contemporary art, he would walk down Dizengoff Street, look at the gallery, spit on the ground, make sure I had seen him, and continue on his way. There is no doubt that the face of this little man, and what he represented, will be missed on the Tel Aviv landscape."**** A shtetl (Yiddish: שטעטל, diminutive form of Yiddish shtot שטאָט, "town", pronounced very similarly to the South German diminutive "Städtle", "little town"; cf. MHG: stetelîn, stetlîn, stetel) was typically a small town with a large Jewish population in pre-Holocaust Central and Eastern Europe. Shtetls (Yiddish plural: שטעטלעך, shtetlekh) were mainly found in the areas which constituted the 19th century Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire, the Congress Kingdom of Poland, Galicia, and Romania. A larger city, like Lemberg or Czernowitz, was called a shtot (Yiddish: שטאָט); a smaller village was called a dorf (Yiddish: דאָרף). The concept of shtetl culture is used as a metaphor for the traditional way of life of 19th-century Eastern European Jews. Shtetls are portrayed as pious communities following Orthodox Judaism, socially stable and unchanging despite outside influence or attacks. The Holocaust resulted in the disappearance of the vast majority of shtetls, through both extermination and mass exodus to the United States and what would become Israel. Origins The history of the oldest Eastern European shtetls began about a millennium ago and saw periods of relative tolerance and prosperity as well as times of extreme poverty, hardships and pogroms. The attitudes and thought habits characteristic of the learning tradition are as evident in the street and market place as the yeshiva. The popular picture of the Jew in Eastern Europe, held by Jew and Gentile alike, is true to the Talmudic tradition. The picture includes the tendency to examine, analyze and re-analyze, to seek meanings behind meanings and for implications and secondary consequences. It includes also a dependence on deductive logic as a basis for practical conclusions and actions. In life, as in the Torah, it is assumed that everything has deeper and secondary meanings, which must be probed. All subjects have implications and ramifications. Moreover, the person who makes a statement must have a reason, and this too must be probed. Often a comment will evoke an answer to the assumed reason behind it or to the meaning believed to lie beneath it, or to the remote consequences to which it leads. The process that produces such a response-- often with lightning speed-- is a modest reproduction of the pilpul process.[1] Not only did the Jews of the shtetl speak a unique language (Yiddish), but they also had a unique rhetorical style, rooted in traditions of Talmudic learning: In keeping with his own conception of contradictory reality, the man of the shtetl is noted both for volubility and for laconic, allusive speech. Both pictures are true, and both are characteristic of the yeshiva as well as the market places. When the scholar converses with his intellectual peers, incomplete sentences a hint, a gesture, may replace a whole paragraph. The listener is expected to understand the full meaning on the basis of a word or even a sound... Such a conversation, prolonged and animated, may be as incomprehensible to the uninitiated as if the excited discussants were talking in tongues. The same verbal economy may be found in domestic or business circles.[1] The shtetl operates on a communal spirit where giving to the needy is not only admired, but expected and essential: The problems of those who need help are accepted as a responsibility both of the community and of the individual. They will be met either by the community acting as a group, or by the community acting through an individual who identifies the collective responsibility as his own... The rewards for benefaction are manifold and are to be reaped both in this life and in the life to come. On earth, the prestige value of good deeds is second only to that of learning. It is chiefly through the benefactions it makes possible that money can "buy" status and esteem.[1] This approach to good deeds finds its roots in Jewish religious views, summarized in Pirkei Avot by Shimon Hatzaddik's "three pillars": On three things the world stands. On Torah, On service [of God], And on acts of human kindness.[2] Tzedaka (charity) is a key element of Jewish culture, both secular and religious, to this day. It exists not only as a material tradition (e.g tzedaka boxes), but also immaterially, as an ethos of compassion and activism for those in need. Material things were neither disdained nor extremely praised in the shtetl. Learning and education were the ultimate measures of worth in the eyes of the community, while money was secondary to status. Menial labor was generally looked down upon as prost, or prole. Even the poorer classes in the shtetl tended to work in jobs that required the use of skills, such as shoe-making or tailoring of clothes. The shtetl had a consistent work ethic which valued hard work and frowned upon laziness. Studying, of course, was considered the most valuable and hard work of all. Learned yeshiva men who did not provide bread and relied on their wives for money were not frowned upon but praised as ideal Jews. Interaction with Gentiles The shtetl's main interaction with Gentile citizens was in trading with the neighboring peasants. There was often animosity towards the Jews from these peasants, resulting in extremely violent pogroms from the Gentiles on the Jews, resulting in many Jewish deaths[when?][where?][who?]. This, among other things, helped foster a very strong "us-them" mentality based on differences between the peoples[vague]. This can be seen in the play Fiddler on the Roof[unreliable source?]. Collapse The May Laws introduced by Tsar Alexander III of Russia in 1882 banned Jews from rural areas and towns of fewer than ten thousand people. In the 20th century revolutions, civil wars, industrialization and the Holocaust destroyed traditional shtetl existence. However, Hasidic Jews have founded new communities in the United States, such as Kiryas Joel and New Square. There is a belief found in historical and literary writings that the shtetl disintegrated before it was destroyed during World War II; however, this alleged cultural break-up is never clearly defined.[who?][3] The shtetl in fiction and folklore Chełm figures prominently in the Jewish humor as the legendary town of fools. Kasrilevke, the setting of many of Sholom Aleichem's stories, and Anatevka, the setting of the musical Fiddler on the Roof (based on other stories of Sholom Aleichem) are other notable fictional shtetls. The 2002 novel Everything Is Illuminated, by Jonathan Safran Foer, tells a fictional story set in the Ukrainian shtetl Trachimbrod. (Trochenbrod) The 1992 children's book Something from Nothing, written and illustrated by Phoebe Gilman, is an adaptation of a traditional Jewish folktale set in a fictional shtetl. In 1996 the Frontline programme Shtetl broadcast; it was about Polish Christian and Jewish relations ****** Tikkun Chatzot (Hebrew: תקון חצות, lit. "Midnight Rectification"), also spelled Tikkun Chatzos, is a Jewish ritual prayer recited each night after midnight as an expression of mourning and lamentation over the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. It is not universally observed, although it is popular among Sephardi and Hasidic Jews. Contents 1 Origin of the custom 2 Service 3 Notes 4 External links Origin of the custom[edit] The Talmudic sages wrote that every Jew should mourn the destruction of the Temple. The origin of the midnight time for prayer and study lies in Psalm 119:62, attributed to David: "At midnight I will rise to give thanks unto thee." It is said that David was satisfied with only "sixty breaths of sleep" (Sukk. 26b), and that he rose to pray and study Torah at midnight.[1] The custom was fixed as a binding Halakha.[citation needed] At first, Mizrahi Jews would add dirges (kinnot) for the destruction only on the three sabbaths that are between the Seventeenth of Tamuz and Tisha B'Av, and not on weekdays.[citation needed] After discussions that questioned this practice of mourning specifically on the Sabbath, it was decided to discontinue the recitation of the kinnot on these days.[citation needed] Rabbi Isaac Luria canceled the customs of mourning on the Sabbath but declared that the Tikkun Chatzot should be said each and every day.[citation needed] The Shulchan Aruch 1:3 states, "It is fitting for every God-fearing person to feel grief and concern over the destruction of the Temple".[2] The Mishnah Berurah comments, "The Kabbalists have discussed at great lengths the importance of rising at midnight [to say the Tikkun Chatzot, learn Torah, and to talk to God] and how great this is".[3] Sephardi communities in Jerusalem have a custom to sit on the floor and recite Tikkun Chatzot after halakhic midday during The Three Weeks.[4][5] This custom is also mentioned in the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch[disambiguation needed], and is practiced in some Ashkenazic communities as well. The Tanya mentions that one should recite Tikkun Chatzot every night if one can. It then suggests that if one cannot do so every night, he should do so on Thursday nights, as a preparation for the Shabbat.[citation needed] Service[edit] Tikkun Chatzot is divided into two parts; Tikkun Rachel and Tikkun Leah, named for the two wives of the Patriarch Jacob. On days when Tachanun is not recited during daytime prayers, only Tikkun Leah is recited (although Sefardim do not recite Tikkun Chatzos at all on Shabbat and Yom Tov[6] ). The Tikkun Chatzot is an individual service; a minyan is not needed for performing it, although some have the custom to recite it with a minyan. At midnight, one sits on the ground or a low stool, takes off his shoes (non-leather shoes are permitted to be worn, as these are not halakhically considered shoes)[citation needed], and reads from the prayer book. Although the ideal time for Tikkun Chatzot is the hour following midnight, Tikkun Rachel may be said until a half (seasonal) hour before `alot hashachar/dawn, and Tikkun Leah until dawn.[7] The Magen Avraham method (also held by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov) is that midnight is six clock hours after nightfall (appearance of 3 medium stars). The method held by Mishnah Berurah is twelve hours after noon (halfway between dawn and dusk). Another way to understand the ideal time for Tikkun Chatzot is at 12:00am midnight (this is another way to understand the Magen Avraham). According to Siddur Beis Yaakov, by Rabbi Yaakov Emden, Psalm 102, the "Prayer of the afflicted," is read before reciting Tikkun Rachel. Afterwards, one begins the actual service by reciting the Viddui confession including Ashamnu, and then one reads Psalm 137, "By the rivers of Babylon," and Psalm 79, "A song of Asaph." Afterwards, verses from the book of Lamentations are read, followed by the kinnot, with customs varying among the communities, the general custom being to recite five or six kinnoth specifically composed for Tikkun Chatzos, some of which were composed by Rabbi Mosheh Alshich. The Tikkun Rachel service is concluded with the reading of Isaiah 52:2, "Shake thyself from the dust..." A shorter version is usually printed in Sephardic siddurim that does not include the "Prayer of the afflicted," and has fewer kinnos. Tikkun Leah consists of various Psalms, and is recited after Tikkun Rachel, or alone on days when tachanun is omitted. The Psalms of Tikkun Leah are Psalm 24, 42, 43, 20, 24, 67, 111, 51, and 126. Psalms 20 and 51 are omitted when Tikkun Rachel is not said. A short prayer concludes the Tikkun. It is common to follow Tikkun Chatzot with learning Torah, in particular Patach Eliyahu or Mishnah. Some learn the last chapter of tractate Tamid. Many study the Holy Zohar. **** Pious individuals recite Tikkun Chatzot which are said slightly before Chatzot (midnight) out of mourning for the Beit HaMikdash. It is split into two parts, known as Tikkun Rachel and Tikkun Leah. Contents 1 The obligation 2 When it should be said 3 How it should be said 4 The feeling with which it should be said 5 Relative precedence 6 Days it is not said 7 What texts should be said? 8 Sources The obligation In order to feel pain over the destruction of the Bet HaMikdash, every night slightly before Chatzot, one should recite Tikkun Chatzot.[1] Although, the Minhag is not to require Tikkun Chatzot and some Achronim justify the minhag, nonetheless, it’s praiseworthy to say it from time to time. [2] Women may say Tikkun Chatzot. [3] When it should be said Ashkenazim hold that it should be said right before Chatzot (midnight) and then one should learn from Chatzot until morning when one can pray. [4] However, Sephardim hold that it should be said at Chatzot of night or afterwards until Olot HaShachar. [5] Tikkun Chatzot should be said before Olot HaShachar. However, many poskim say that one may say Tikkun Leah after Olot HaShachar. [6] During the three weeks (Ben HaMetzarim), Tikkun Chatzot should be said after Chatzot of the day.[7] How it should be said It is the practice to say Tikkun Chatzot while sitting on the floor near a doorpost that has a mezuzah. One shouldn't sit directly on the ground rather one should sit on a cloth, pillow, or small bench. If the floor is tiled, one can be lenient to sit directly on the floor. [8] The Minhag is to place ashes on one's head in the area where the Tefillin Shel Rosh is placed. [9] Another practice is to not to wear shoes during Tikkun Chatzot. [10] Some had the practice to say Tikkun Chatzot communally in shul. Even though some oppose the practice, it has what to rely on and has it's benefits. [11] The feeling with which it should be said One should be pained over the destruction of the Temple. [12] However, in general, when one is learning or praying one should do so with happiness.[13] Relative precedence If one only has time for Tikkun Chatzot and Selichot, one should say Tikkun Chatzot. [14] If one only has time for Tikkun Chatzot and learning torah, one should say Tikkun Chatzot. [15] If saying Tikkun Chatzot will prevent one from being able to wake up for praying at HaNetz (Vatikin), nonetheless, one should say Tikkun Chatzot and pray after HaNetz. However, even if one is waking up to pray after HaNetz, one must ensure to say Shema before the latest time for Shema and pray Shemona Esreh before the latest time for Shemona Esreh.[16] Days it is not said On the following nights no Tikkun Chatzot is said: Shabbat, [17] Rosh HaShana, Yom Kippur, Pesach (Yom Tov and Chol HaMoed), Shavuot, Sukkot (just Yom Tov), and Shemini Aseret. [18] On the following nights no Tikkun Rachel is said, but Tikkun Leah is still said: days when there's no Tachanun, Chol HaMoad Sukkot, Asert Yemei Teshuva, year of Shemittah in Israel, day after the Molad before Rosh Chodesh, [19] and days of Sefirat HaOmer. [20] In the following cases no Tikkun Rachel is said: at a mourner's house, the house of a groom, and the father of a baby boy the night before the milah, Sandak (holder of the baby), and Mohel of a Brit Milah.[21] What texts should be said? A free copy of the text can be found from the Siddur Torat Emet (pdf). **** The Power of Tikkun Chatzot A person in this world is constantly being robbed of his dearest possessions - inner peace and tranquility. But there's a way to recover them from the robber... By: Rabbi Nissan Dovid Kivak Update date: 12/20/2020, 19:02 0 Google +0 2 9 Translated by Aaron Yoseph The Divine concealment is called the “two birds” and this is man’s reality in this world. “And it states in the Zohar HaKadosh: "And when the night is split (i.e. at midnight), then a call goes out, 'Like birds caught in a trap, so too are men caught.'” Just like birds that are caught in a trap, so too do men stumble. They didn't intend to, it was accidental, but the forces of evil caught them. This is a man’s life in this world, day after day. Misery and depression. Even if there’s no real bad, everything’s in order, just that here and there things didn’t work out, and he worries about a few pennies, and there is some hatred in his home, and the grandchildren and the grandparents – there’s always some new thing to worry about. It’s all hot straight from the oven. A man just needs to sort this one thing out now, and then everything will be okay. This is the birds in a trap, where the supernal light is closed off. At midnight the Attribute of Mercy is aroused. Although evil wants to pull us down, confusing us with worries and depressing thoughts, we can overcome. With the holiness of Chatzos, midnight lamentations, with the power of learning Torah and clinging to Hashem especially in the wee hours before daybreak, we uplift ourselves from the trap that tries to ensnare us. Rebbe Nachman tells about the rich Jew who had everything stolen from him. He picked himself up and gathered up what he had left and opened up a small shop to make a living. He wouldn’t be rich, but at least he could make a living. The robber returned and stole everything he had in the shop. So he started traveling around selling chickens and clothing. He had his bag on his back, and the robber rides up again on his horse, “Hey, Jew! Give me your bag.” He stole everything he had. Let’s say that he accepted it all with love, and was grateful that he still had his life. “Baruch Hashem I’m still alive!” Suddenly he sees that the robber fell off his horse. The horse panicked and happened to kick him in the head, and he was a robber no more. The Jew went to get his possessions back, but found there many more of the robbers packages – a fortune, even more money than he had had at first. So it is with all of us. All the stress of where to live, of making a living, of paying tuition for our children's Yeshivas – who can understand what a person goes through? He thinks that he’s been beaten. But there is no injustice. There are soul corrections that a person needs to go through – that he has to stumble in all the things that break him down and crush him. In the end, we recover all that was stolen, plus a million times more than we lost. But in the meanwhile – we have to strengthen ourselves. The Zohar HaKadosh speaks about getting up for Chatzos. The person who has the strength to overpower these "two birds" is the one who can get up at night. He’s awake at night and he says Tikkun Chatzos and learns something – whatever it may be. He stops chattering, and does something to serve Hashem. Whoever doesn’t get up is like the bird caught in the trap – he’s the person caught in a trap, and he doesn’t hear the niggun of the Torah. It would be easy for him to see something and be happy, but he doesn’t do it. So he lives with lethargy day after day, and the lethargy grows together with depression, and he’s caught like a bird. “I don’t know what happened to me!” So too people stumble - when they don’t have the power of Chatzos. At midnight King David’s harp plays – this is the power to receive the Torah. It’s a wondrous niggun, where you know that Hashem took us out of slavery in Egypt. Emuna is aroused, and you know why you are alive. You know that everything you’re going through is nonsense. This is how it is. Nu – when you need to do something, make yourself serious, pretend – relate to whatever it is normally – with Emuna. “Who can do anything to me?” What are you worried about? But when a person doesn’t have the merit of Chatzos, he has no way to escape the trap. There are bad things that need fixing, but there are sparks to elevate us - that's what saying Tikkun Chatzos is all about. Midnight Lamentations help us recover what the "robber" stole from us; we get back the Beis Hamikdash, the Holy Temple. ebay5254 folder 195