-40%

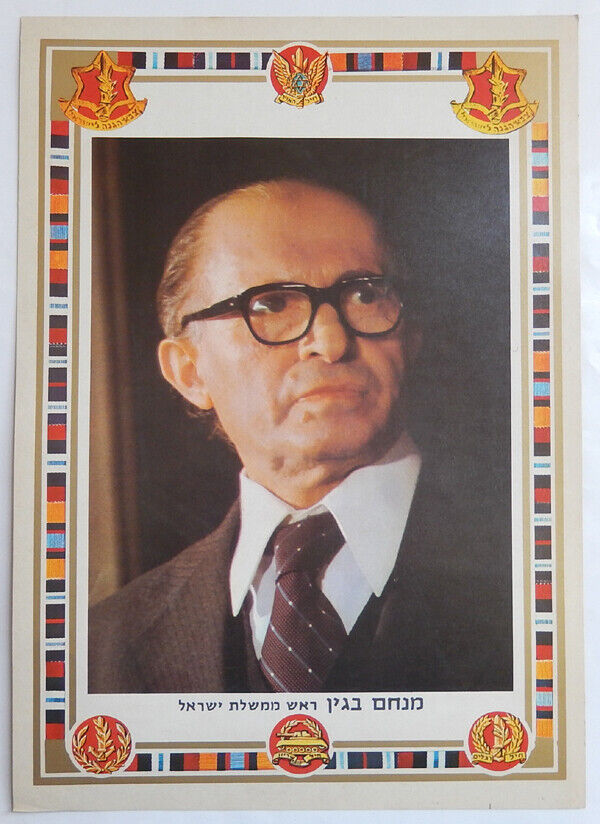

MENACHEM BEGIN ISRAEL PRIME MINSTER POSTER JUDAICA IDF ARMY RIBBON 1970'S

$ 20.59

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

MENACHEM BEGIN ISRAEL PRIME MINSTER POSTER 1970'SThis is a poster portrait of MENACHEM BEGIN. Capture below the photo reads "Menachem Begin Israel's Prime Minister" . The poster is decorated with Israeli army signs and war ribbons. This poster is from the 1970's after Begin was elected. Very good condition. Size: 13.5x10 inch.

Buyer to pay .00 shipping international registered air mail.

Payment accepted via Paypal

Authenticity 100% Guaranteed

Please have a look at my other listings

Good Luck!

Formation and Begin years The Likud was formed as a secular party[22] by an alliance of several right-wing parties prior to the 1973 elections—Herut, the Liberal Party, the Free Centre, the National List, and the Movement for Greater Israel. Herut had been the nation's largest right-wing party since growing out of the Irgun in 1948. It had already been in coalition with the Liberals since 1965 as Gahal, with Herut as the senior partner. Herut remained the senior partner in the new grouping, which was given the name Likud, meaning "Consolidation", as it represented the consolidation of the Israeli right.[27] It worked as a coalition under Herut's leadership until 1988, when the member parties merged into a single party under the Likud name. From its establishment in 1973, Likud enjoyed great support from blue-collar Sephardim who felt discriminated against by the ruling Alignment. Likud made a strong showing in its first elections in 1973, reducing the Alignment's lead to 12 seats. The party went on to win the 1977 elections, finishing 11 seats ahead of the Alignment. Begin was able to form a government with the support of the religious parties, consigning the left-wing to opposition for the first time since independence. A former leader of the hard-line paramilitary Irgun, Begin helped initiate the peace process with Egypt, which resulted in the 1978 Camp David Accords and the 1979 Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty. Likud was reelected with a significantly reduced mandate in 1981. Likud has long been a loose alliance between politicians committed to different and sometimes opposing policy preferences and ideologies.[28][29] The 1981 elections highlighted divisions that existed between the populist wing of Likud, headed by David Levy of Herut, and the Liberal wing,[30] who represented a policy agenda of the secular bourgeoisie.[28] Shamir, Netanyahu's first term, and Sharon Begin resigned in October 1983 and was succeeded as Likud leader and Prime Minister by Yitzhak Shamir. Shamir, a former commander of the Lehi underground, was widely seen as a hard-liner with an ideological commitment both to the settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the growth of which he encouraged, and to the idea of aliyah, facilitating the mass immigration of Jews to Israel from Ethiopia and the former Soviet Union. Although Shamir lost the 1984 election, the Alignment was unable to form a government on its own. Likud and the Alignment thus formed a national unity government, with Peres as Prime Minister and Shamir as foreign minister. After two years, Peres and Shamir switched posts. This government remained in power through 1990, when the Alignment pulled out and Shamir stitched together a right-wing coalition that held on until its defeat in 1992 by Labor. Shamir retired shortly after losing the election. His successor, Benjamin Netanyahu, became the third Likud Prime Minister in May 1996, following the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin. Netanyahu proved to be less hard-line in practice than he made himself out to be rhetorically, and felt pressured by the United States and others to enter negotiations with the Palestine Liberation Organization and Yasser Arafat, despite his harsh criticism of the Oslo accords and hawkish stance in comparison to Labor. In 1998, Netanyahu reluctantly agreed to cede territory in the Wye River Memorandum. While accepted by many in the Likud, some Likud MKs, led by Benny Begin (Menachem Begin's son), Michael Kleiner and David Re'em, broke away and formed a new party, named Herut – The National Movement, in protest. Yitzhak Shamir (who had expressed harsh disappointment in Netanyahu's leadership), gave the new party his support. Less than a year afterward, Netanyahu's coalition collapsed, resulting in the 1999 election and Labor's Ehud Barak winning the premiership on a platform of immediate settlement of final status issues. Likud spent 1999–2001 on the opposition benches. Barak's "all-or-nothing" strategy failed, however, and early elections for Prime Minister were called for March 2001. Surprisingly, Netanyahu declined to be the Likud candidate for Prime Minister, meaning that the fourth Likud premier would be Ariel Sharon. Sharon, unlike past Likud leaders, had been raised in a Labor Zionist environment and had long been seen as something of a maverick. In the face of the Second Intifada, Sharon pursued a varied set of policies, many of which were controversial even within the Likud. The final split came when Sharon announced his policy of unilateral disengagement from Gaza and parts of the West Bank. The idea proved extremely divisive within the party. Kadima split Sharon's perceived shift to the political center, especially in his execution of the Disengagement Plan, alienated him from some Likud supporters and fragmented the party. He faced several serious challenges to his authority shortly before his departure. The first was in March 2005, when he and Netanyahu proposed a budget plan that met fierce opposition, though it was eventually approved. The second was in September 2005, when Sharon's critics in Likud forced a vote on a proposal for an early leadership election, which was defeated by 52% to 48%. In October, Sharon's opponents within the Likud Knesset faction joined with the opposition to prevent the appointment of two of his associates to the Cabinet, demonstrating that Sharon had effectively lost control of the Knesset and that the 2006 budget was unlikely to pass. The next month, Labor announced its withdrawal from Sharon's governing coalition following its election of the left-wing Amir Peretz as leader. On 21 November 2005, Sharon announced he would be leaving Likud and forming a new centrist party, Kadima. The new party included both Likud and Labor supporters of unilateral disengagement. Sharon also announced that elections would take place in early 2006. As of 21 November seven candidates had declared themselves as contenders to replace Sharon as leader: Netanyahu, Uzi Landau, Shaul Mofaz, Yisrael Katz, Silvan Shalom and Moshe Feiglin. Landau and Mofaz later withdrew, the former in favour of Netanyahu and the latter to join Kadima. Netanyahu's second term Netanyahu went on to win the chairmanship elections in December, obtaining 44.4% of the vote. Shalom came in a second with 33%, leading Netanyahu to guarantee him second place on the party's list of Knesset candidates. Shalom's perceived moderation on social and foreign-policy issues were considered to be an electoral asset. Observers noted that voter turnout in the elections was particularly low in comparison with past primaries, with less than 40 percent of the 128,000 party members casting ballots. There was much media focus on far-right candidate Moshe Feiglin achieving 12.4% of votes. The founding of Kadima was a major challenge to the Likud's generation-long status as one of Israel's two major parties. Sharon's perceived centrist policies have drawn considerable popular support as reflected by public opinion polls. The Likud is now led by figures who oppose further unilateral evacuations, and its standing in the polls has suffered. After the founding of Kadima, Likud came to be seen as having more of a right-wing tendency than a moderate centre-right one. However, there exist several parties in the Knesset even more right-wing than the post-Ariel Sharon Likud. A truck canvassing for Likud in Jerusalem in advance of the 2006 election Prior to the 2006 election, the party's Central Committee relinquished control of selecting the Knesset list to the "rank and file" members at Netanyahu's behest.[31] The aim was to improve the party's reputation, as the central committee had gained a reputation for corruption.[32] In the election, the Likud vote collapsed in the face of the Kadima split. Other right-wing nationalist parties such as Yisrael Beiteinu gained votes, with Likud coming only fourth place in the popular vote, edging out Yisrael Beiteinu by only 116 votes. With only twelve seats, Likud was tied with the Shas for the status of third-largest party. In the 2009 Israeli legislative election, Likud won 27 seats, a close second-place finish to Kadima's 28 seats, and leading the other parties. After more than a month of coalition negotiations, Benjamin Netanyahu was able to form a government and become Prime Minister. "Pride in the Likud", a political advocacy group of LGBT conservatives affiliated with the party, was founded in 2011. Following the appointment of Amir Ohana as the Likud's first openly gay member in the Knesset, in December 2015, Netanyahu said he was "proud" to welcome him into parliament.[33] A leadership election was held on 31 January 2012, with Netanyahu defeating Feiglin.[34] Likud generally advocates free enterprise and nationalism, but it has sometimes compromised these ideals in practice, especially as its constituency has changed. Its support for populist economic programs are at odds with its free enterprise tradition, but are meant to serve its largely nationalistic, lower-income voters in small towns and urban neighborhoods.[62][63] On religion and state, Likud has a moderate stance,[63] and supports the preservation of status quo. With time, the party has played into the traditional sympathies of its voter base, though the origins and ideology of Likud are secular.[64] Religious parties have come to view it as a more comfortable coalition partner than Labor.[63] Likud promotes a revival of Jewish culture, in keeping with the principles of Revisionist Zionism. Likud emphasizes such Israeli nationalist themes as the use of the Israeli flag and the victory in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. In July 2018, Likud lawmakers backed controversial Nation-State bill into law which declaring Israel as 'nation-state of the Jewish people'.[65][66] Likud publicly endorses press freedom and promotion of private sector media, which has grown markedly under governments Likud has led. A Likud government headed by Ariel Sharon, however, closed the popular right-wing pirate radio station Arutz Sheva ("Channel 7"). Arutz Sheva was popular with the Jewish settler movement and often criticised the government from a right-wing perspective. Historically, the Likud and its pre-1948 predecessor, the Revisionist movement advocated secular nationalism. However, the Likud's first prime minister and long-time leader Menachem Begin, though secular himself, cultivated a warm attitude to Jewish tradition and appreciation for traditionally religious Jews—especially from North Africa and the Middle East. This segment of the Israeli population first brought the Likud to power in 1977. Many Orthodox Israelis find the Likud a more congenial party than any other mainstream party, and in recent years also a large group of Haredim, mostly modern Haredim, joined the party and established The Haredi faction in the Likud. Menachem Begin (Hebrew: מְנַחֵם בֵּגִין Menaḥem Begin (About this soundlisten (help·info)); Polish: Mieczysław Biegun (Polish birth name), Polish: Menachem Begin (Polish documents, 1931–1937);[1] Russian: Менахем Вольфович Бегин Menakhem Volfovich Begin; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel. Before the creation of the state of Israel, he was the leader of the Zionist militant group Irgun, the Revisionist breakaway from the larger Jewish paramilitary organization Haganah. He proclaimed a revolt, on 1 February 1944, against the British mandatory government, which was opposed by the Jewish Agency. As head of the Irgun, he targeted the British in Palestine.[2] Later, the Irgun fought the Arabs during the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and its chief Begin was also noted as "leader of the notorious terrorist organisation" by British government and banned from entering the United Kingdom.[3] Begin was elected to the first Knesset, as head of Herut, the party he founded, and was at first on the political fringe, embodying the opposition to the Mapai-led government and Israeli establishment. He remained in opposition in the eight consecutive elections (except for a national unity government around the Six-Day War), but became more acceptable to the political center. His 1977 electoral victory and premiership ended three decades of Labor Party political dominance. Begin's most significant achievement as Prime Minister was the signing of a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, for which he and Anwar Sadat shared the Nobel Prize for Peace. In the wake of the Camp David Accords, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which was captured from Egypt in the Six-Day War. Later, Begin's government promoted the construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Begin authorized the bombing of the Osirak nuclear plant in Iraq and the invasion of Lebanon in 1982 to fight PLO strongholds there, igniting the 1982 Lebanon War. As Israeli military involvement in Lebanon deepened, and the Sabra and Shatila massacre, carried out by Christian Phalangist militia allies of the Israelis, shocked world public opinion,[4] Begin grew increasingly isolated.[5] As IDF forces remained mired in Lebanon and the economy suffered from hyperinflation, the public pressure on Begin mounted. Depressed by the death of his wife Aliza in November 1982, he gradually withdrew from public life, until his resignation in October 1983. Menachem Begin was born to Zeev Dov and Hassia Biegun in what was then Brest-Litovsk in the Russian Empire (today Brest, Belarus). He was the youngest of three children.[6] On his mother's side he was descended from distinguished rabbis. His father, a timber merchant, was a community leader, a passionate Zionist, and an admirer of Theodor Herzl. The midwife who attended his birth was the grandmother of Ariel Sharon.[7] After a year of a traditional cheder education Begin started studying at a "Tachkemoni" school, associated with the religious Zionist movement. In his childhood, Begin, like most Jewish children in his town, was a member of the Zionist scouts movement Hashomer Hatzair. He was a member of Hashomer Hatzair until the age of 13, and at 16, he joined Betar.[8] At 14, he was sent to a Polish government school,[9] where he received a solid grounding in classical literature. Begin studied law at the University of Warsaw, where he learned the oratory and rhetoric skills that became his trademark as a politician, and viewed as demagogy by his critics.[10] Begin reviews a Betar lineup in Poland in 1939. Next to him is Moshe (Munya) Cohen During his studies, he organized a self-defense group of Jewish students to counter harassment by anti-Semites on campus.[11] He graduated in 1935, but never practiced law. At this time he became a disciple of Vladimir "Ze'ev" Jabotinsky, the founder of the nationalist Revisionist Zionism movement and its youth wing, Betar.[12] His rise within Betar was rapid: at 22, he shared the dais with his mentor at the Betar World Congress in Kraków. The pre-war Polish government actively supported Zionist youth and paramilitary movements. Begin's leadership qualities were quickly recognised. In 1937[citation needed] he was the active head of Betar in Czechoslovakia and became head of the largest branch, that of Poland. As head of Betar's Polish branch, Begin traveled among regional branches to encourage supporters and recruit new members. To save money, he stayed at the homes of Betar members. During one such visit, he met his future wife Aliza Arnold, who was the daughter of his host. The couple married on 29 May 1939. They had three children: Binyamin, Leah and Hassia.[13][14] Living in Warsaw in Poland, Begin encouraged Betar to set up an organization to bring Polish Jews to Palestine. He unsuccessfully attempted to smuggle 1,500 Jews into Romania at the end of August 1939. Returning to Warsaw afterward, he left three days after the German 1939 invasion began, first to the southwest and then to Wilno. NKVD mugshots of Menachem Begin, 1940 In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, Begin, in common with a large part of Warsaw's Jewish leadership, escaped to Wilno (today Vilnius), then eastern Poland, to avoid inevitable arrest. The town was soon occupied by the Soviet Union, but from 28 October 1939, it was the capital of the Republic of Lithuania. Wilno was a predominately Polish and Jewish town; an estimated 40 percent of the population was Jewish, with the YIVO institute located there. As a prominent pre-war Zionist and reserve status officer-cadet, on 20 September 1940, Begin was arrested by the NKVD and detained in the Lukiškės Prison. In later years he wrote about his experience of being tortured. He was accused of being an "agent of British imperialism" and sentenced to eight years in the Soviet gulag camps. On 1 June 1941 he was sent to the Pechora labor camps in Komi Republic, the northern part of European Russia, where he stayed until May 1942. Much later in life, Begin recorded and reflected upon his experiences in the interrogations and life in the camp in his memoir White Nights. On 1 February 1944, the Irgun proclaimed a revolt. Twelve days later, it put its plan into action when Irgun teams bombed the empty offices of the British Mandate's Immigration Department in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa. The Irgun next bombed the Income Tax Offices in those three cities, followed by a series of attacks on police stations in which two Irgun fighters and six policemen were killed. Meanwhile, Lehi joined the revolt with a series of shooting attacks on policemen.[17] Palestine Police Force wanted poster of Irgun and Lehi members. Begin appears at the top left. The Irgun and Lehi attacks intensified throughout 1944. These operations were financed by demanding money from Jewish merchants and engaging in insurance scams in the local diamond industry.[18] Begin in the guise of "Rabbi Sassover" with wife Aliza and son Benyamin-Zeev, Tel Aviv, December 1946 Begin with Irgun members, 1948 In 1944, after Lehi gunmen assassinated Lord Moyne, the British Resident Minister in the Middle East, the official Jewish authorities, fearing British retaliation, ordered the Haganah to undertake a campaign of collaboration with the British. Known as The Hunting Season, the campaign seriously crippled the Irgun for several months, while Lehi, having agreed to suspend their anti-British attacks, was spared. Begin, anxious to prevent a civil war, ordered his men not to retaliate or resist being taken captive, convinced that the Irgun could ride out the Season, and that the Jewish Agency would eventually side with the Irgun when it became apparent the British government had no intention of making concessions. Gradually, shamed at participating in what was viewed as a collaborationist campaign, the enthusiasm of the Haganah began to wane, and Begin's assumptions were proven correct. The Irgun's restraint also earned it much sympathy from the Yishuv, whereas previously it had been assumed by many that it had placed its own political interests before those of the Yishuv. Altalena and the 1948 Arab–Israeli War Altalena on fire after being shelled near Tel-Aviv After the Israeli Declaration of Independence on 14 May 1948 and the start of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Irgun continued to fight alongside Haganah and Lehi. On 15 May 1948, Begin broadcast a speech on radio declaring that the Irgun was finally moving out of its underground status.[23] On 1 June Begin signed an agreement with the provisional government headed by David Ben-Gurion, where the Irgun agreed to formally disband and to integrate its force with the newly formed Israel Defense Forces (IDF),[citation needed] but was not truthful of the armaments aboard the Altalena as it was scheduled to arrive during the cease-fire ordered by the United Nations and therefore would have put the State of Israel in peril as Britain was adamant the partition of Jewish and Arab Palestine would not occur. This delivery was the smoking gun Britain would need to urge the UN to end the partition action. In August 1948, Begin and members of the Irgun High Command emerged from the underground and formed the right-wing political party Herut ("Freedom") party.[29] The move countered the weakening attraction for the earlier revisionist party, Hatzohar, founded by his late mentor Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Revisionist 'purists' alleged nonetheless that Begin was out to steal Jabotinsky's mantle and ran against him with the old party. The Herut party can be seen as the forerunner of today's Likud. In November 1948, Begin visited the US on a campaigning trip. During his visit, a letter signed by Albert Einstein, Sidney Hook, Hannah Arendt, and other prominent Americans and several rabbis was published which described Begin's Herut party as "terrorist, right-wing chauvinist organization in Palestine,"[30] "closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties" and accused his group (along with the smaller, militant, Stern Gang) of preaching "racial superiority" and having "inaugurated a reign of terror in the Palestine Jewish community".[31][32] In the first elections in 1949, Herut, with 11.5 percent of the vote, won 14 seats, while Hatzohar failed to break the threshold and disbanded shortly thereafter. This provided Begin with legitimacy as the leader of the Revisionist stream of Zionism. During the 1950s Begin was banned from entering the United Kingdom, as the British government regarded him as "leader of the notorious terrorist organisation Irgun"[33]