-40%

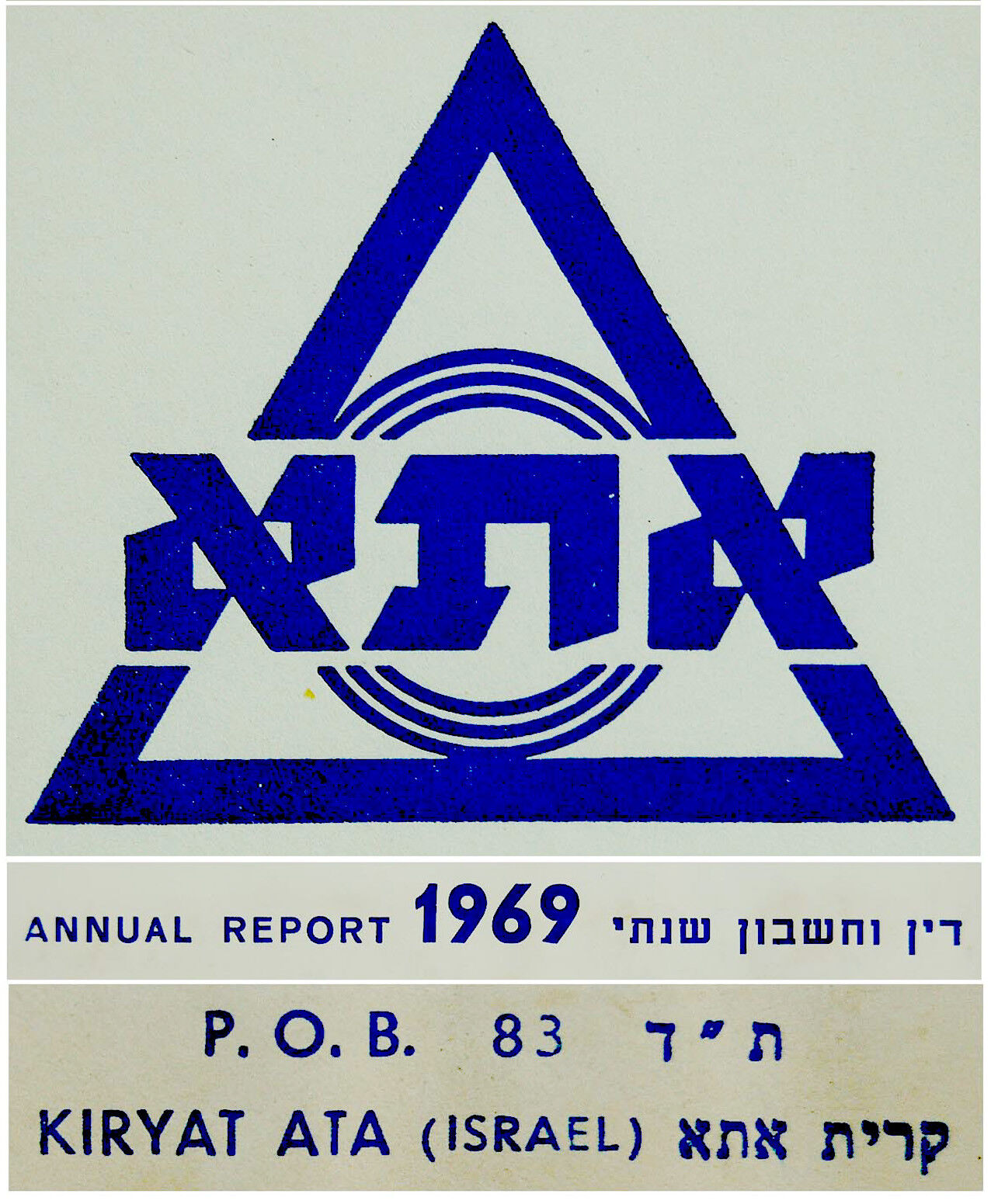

1969 ATA Advertise ENVELOPE COVER Israel TEXTILE Factory HEBREW Industry LOGO

$ 23.76

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

Here for sale is an ORIGINAL VINTAGE advertising Jewish - Judaica - Israeli 50 YEARS OLD empty BIG ENVELOPE - COVER which was issued in 1969 ( Clearly dated )

by the quite mythological Israeli textile factory "ATA" to contain and dispache its 1969 ANNUAL REPORT. It has the mythological "ATA" logo and the "ATA" P.O.BOX adress . Around 12 x 9 " ( not accurate ) . Very good condition.

Somewhat stained. ( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images )

.

Will be shipped in a special protective rigid sealed package.

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal & All credit cards.

SHIPPMENT

:

SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 19 .

Will be shipped in a special protective rigid sealed package

.

Will be sent around 5-10 days after payment .

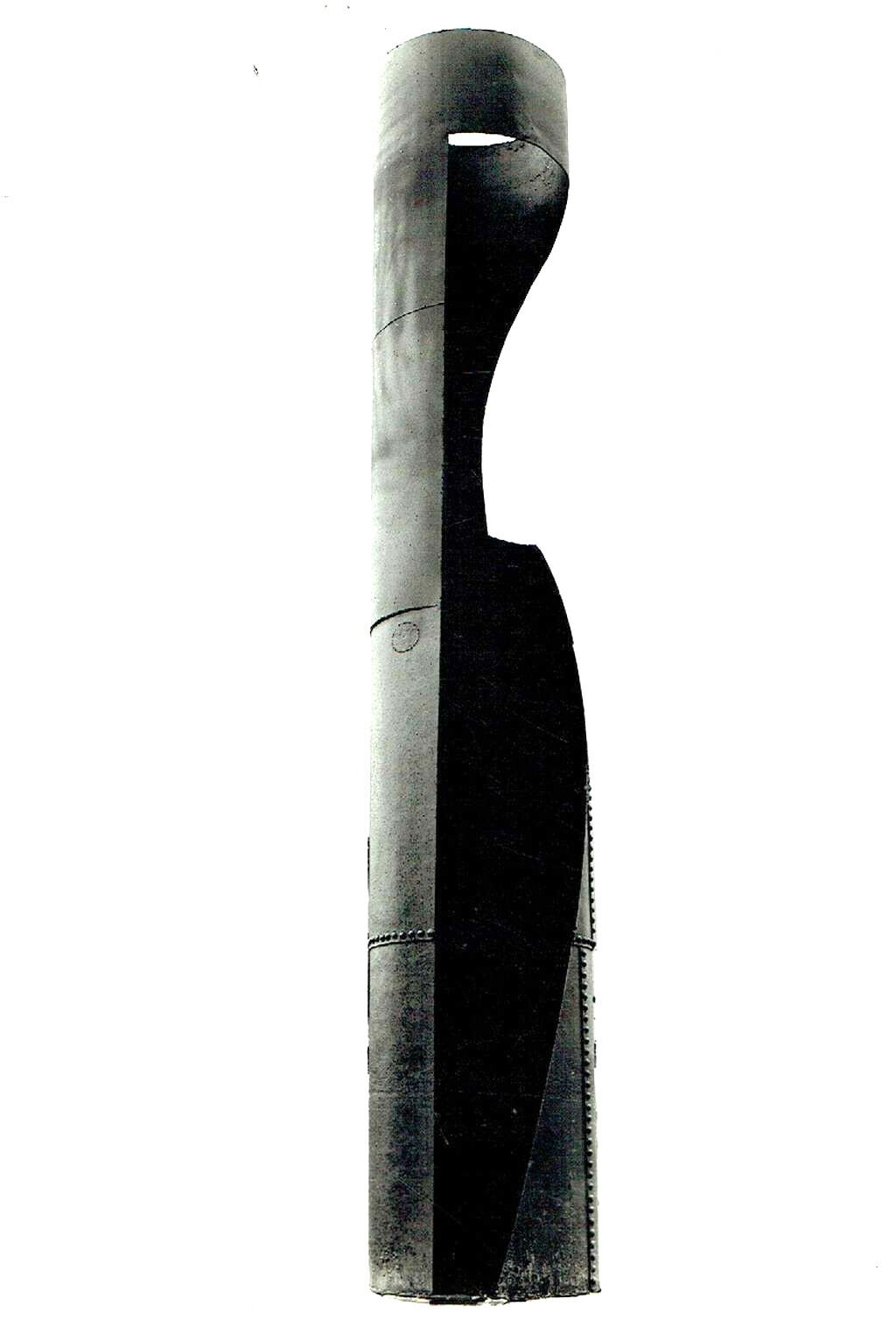

The story of the Ata textile factory mirrors the changes that took place in Israeli society from the 1930s to the 1980s. In these 50 years a dramatic change took place in the perception of work, employment and social responsibility in Israeli society and economy: from a society based on a worldview that drew its sources and inspiration from culture and socialist working relations, which regarded the private and governmental employer as responsible for his or her employment, and the welfare and education of the employee, Israel became a state which had assimilated the capitalistic model of the American economist Milton Friedman and his students at the University of Chicago who raised the banner of privatization, freeing the economy of governmental supervision and making large cuts in welfare budgets. The history of the textile factory that was founded in Kfar Ata in 1934 by the Moller family, Jewish industrialists from Czechoslovakia, based on a perception that combined economic pragmatism, liberal Zionism and social enlightenment, serves as a litmus test which clearly reveals the economic, political and social changes that took place in Israeli society and the results of these changes in a brief and discrete period. Even before radical changes took place in Israel's economic and political structure, the happenings in the Ata factory concretized the three governing powers in Israeli economy: one comprised the industrialists, the second - the trade unions, and the third - the government. The story of the Ata factory is also the built-in suspense story between these three powers and the attempts, at times heroic and dramatic - to create equilibrium. In addition to the socioeconomic story, the history also relates the story of the factory and its products - fabric, clothing and domestic textile, the story of the appearnce of Israeli society and its sectoral division. Israel's workers and soldiers wore Ata clothing, as did members of youth movements, while urban and bourgeois Israelis preferred more stylish clothing. Ata rendered three symbols that are engraved on Israeli cultural memory: the pride in being a worker, the struggle of workers to retain to their workplace, and work clothes. The exhibit seeks to present these memories in a broad historical context, uncover the interconnection between these elements, and reconstruct a period never to return return in the history of the State of Israel. The exhibition "ATA - a story about a factory, fashion and a dream," which opened October 6 at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv, could not have come at a better time than now, amid a period of social protest, say the curators. "ATA symbolizes a longing for the Israel of the past, the Israel that takes care of its workers," says Eran Litvin. "In 1957 there was a major crisis at the factory because they were threatening to fire people in the name of efficiency, and the workers didn't let it happen. Throughout its years, the employers were committed to their employees, and in the 1980s the disintegration and privatization began." Litvin curated the exhibition with Monica Lavi, the curator of the Nachum Gutman Art Museum in Tel Aviv. I wrote about ATA last year, the 25th anniversary of the closing of the first Israeli textile factory, that was a source of pride for thousands of Israelis. At the time, I had trouble understanding the strong feelings that the manufacturer's cotton shorts gave rise to among the designers, journalists and fashion researchers who grew up with them, or their amazement over a cotton button-down shirt. Some of them recalled uncompromising quality, and some recalled significant childhood moments. Some described the unique experience of purchasing an item you believed you would keep for a lifetime. In a preliminary visit to the storerooms of the Eretz Israel Museum, it was exciting simply to see the preserved clothes, folded in white silk papers in a room with temperature- and humidity-controlled conditions. With the exception of the clothing archive of the Shenkar College of Engineering and Design, which is also not open to the general public, there is no museum or archive that lets the public view collections of clothing that embody our political, social and aesthetic history. But even there, between the iconic blue shirt and a bright flowered dress, I wondered about their beauty and value in terms of fashion and culture. Is the uninspired cotton shirt really so beautiful? And doesn't the dress, made in the 1960s spirit of freedom, look pretentious and ridiculous today? What can they say about fashion during the first decades of the state? The planning (at the time, fashion designers were generally called fashion planners ) was focused entirely on developing utilitarian and durable clothes that could fill their roles (work, leisure or combat ) and justify their prices. Nobody from the factory, including the planners, was concerned about beauty, taste or creative whimsy. One of the primary values behind ATA clothing was national solidarity. The factory's fashionable products in its early years included a drill fabric called "army" and a cotton satin called "officer." The colors included khaki, blue, white and black; khaki and blue were the most popular. "The names of the fabrics attest to their nature," wrote Ayala Raz, a fashion researcher and the author of "Halifot Ha'itim" ("Changing Styles: 100 Years of Fashion in Eretz Israel," Yedioth Books ), in the text accompanying the exhibition. "These are not expensive fabrics for fashionable clothes, but fabrics meant for work clothes and military uniforms." The factory received its name, which is an acronym for the Hebrew "Arigei Totzeret Artzeinu" ("fabrics manufactured in our land" ), from writer S.Y. Agnon. Erich Moller, one of the factory's founders, said the novelist invented the phrase over a shot of cognac in Moller's home, after mulling the different Hebrew spellings of the factory's name and the village of Ata, where it was located. In the few advertisements produced during the factory's early years, the Association for Israeli Products used patriotic slogans to promote its wares, and focused more on values than on marketing. "For us, the children and youth of the 1930s and the 1940s, ATA was an inseparable part of Eretz Israel," wrote Menachem Talmi in the daily Maariv in 1983. "For us ATA was khaki pants that we rolled up; the khaki shirts we wore proudly on Shabbat; the rough but strong work clothes that withstood oil stains and limestone specks and did not wear out quickly." History through textiles What will older visitors gain from seeing these pieces of memory, beyond a twinge of nostalgia? And for the younger people who were born into an abundance of stylish clothes, could plain cotton arouse similar emotion in them? "For me it's not a fashion exhibition but a historical one," explains Lavi, 50. Her co-curator, Litvin, 36, initiated the exhibition, which will be on display until the end of March 2012. Although the exhibit contains quite a few original items of clothing from various periods in the factory's history, this was not the curators' main concern. They were more focused on the story of the factory as a representative of the social, economic and political processes that took place during its years of operation, from 1934 to 1985. Lavi says she was drawn to stage the exhibition now because it could "draw a very distinct fault line in Israeli society, which only rarely can be marked so clearly. A line that symbolizes Israel's transition from a society with mutual responsibility that recognizes the value of work and favors reasonable class disparities, to a society with a very strong capitalist orientation. In ATA's case, this was reflected in the factory's closing, which was a traumatic event for the workers and for all of Israeli society." The curators divided the exhibition into two main chapters. The first part is devoted to the factory and its founders, and the second part to the fashion it created. Each is divided into subchapters. "The first chapter is about the two central figures behind the factory - cousins Erich Moller and Hans Moller, and their worldview," says Litvin. The family had a spinning mill in Czechoslovakia; Hans sought to open the factory in Palestine as part of a Zionist initiative. The exhibition seeks to depict the atmosphere inside the factory during its first years, through photographs and documents. These include a beautiful 1962 series of black-and-white images by photographer Anna Rivkin Brick. She focused on the workers along the production line, including cutters, sewers, fashion designers, quality control specialists and distributors. Rivkin gave the workers "a kind of holy aura, similar to how they used to depict workers in the late 19th century - as part of a European tradition that sanctifies work and the worker, the man with golden hands," says Lavi. The exhibition also focuses on the major strike at the factory, in 1957. "That was the breaking point: The threat of dismissals to promote efficiency, which Hans Moller tried to lead, was something new in the country at the time," says Litvin. "The Histadrut labor federation intervened, and the strike ended with a compromise: They fired fewer workers than planned." Dress code Only later, after the show's first chapters, did the curators create the chapter dedicated to the factory's fashions. Here, khaki uniforms for the British army, children's and women's clothes, the well-known work clothes of the pioneers and the settlers, and of course the "kova tembel" (the popular dome-shaped "fool's hat" identified with kibbutzniks and others ), are displayed in transparent Perspex boxes. The exhibition even includes one of the factory's first spools ofthread. "This is a unique factory that formulated the state's dress code for a certain period," says Lavi. "And it was done based on the political, social and ethical code." In order to understand how this dress code was introduced, adds Lavi, it's enough to mention that Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion was the model for the factory's khaki clothing. "The clothes were identified with the government and the pioneering spirit," she continues. "The photos of Ben-Gurion from the period when he was a law student in Istanbul, for example, show him in a three-piece suit. In other words, he was familiar with the proper European dress code. But here in Palestine, the 'new Jew' and the 'new Israeli' needed a different dress code, and it had to be invented, just as they needed to invent a language for Israeli art. And that's one of the things ATA did." "Khaki clothing created a social revolution and blurred the class differences," wrote Raz in her book. "Khaki was not only a color, it was a worldview that demanded simplicity and thrift, along with national pride and a willingness to embark on military campaigns." While some people see values of class equality and national unity in this, Lavi sees ATA's vision of Israeliness differently. "The factory's khaki clothing, along with the kova tembel, were the uniform of the hegemonic Israeli, but of course there were different types of Israelis: There were Tel Aviv Israelis; there were religious Israelis; there were also Arabs who were not yet considered Israelis, but their style of dress also had an influence; and of course there were the new immigrants. "This was an attempt to create a uniform Israeli look. In other words, you're no longer Yemenite, Russian, Polish or Moroccan. You've become an Israeli. That's an entity that didn't exist at the time, and had to be created. That was part of inventing Israeliness. Suddenly they explain to you that the general public has something in common, they tell you exactly how everyone should look, and that look is simple and not pricey. You can become an Israeli even if you have nothing, because it really costs pennies. It's interesting to consider the sociological story and the history of hegemony and indoctrination concealed beneath the clothes." The period of the first two decades of the state is considered ATA's golden age. The factory had stores all over the country and dictated the local dress code. "But it's impossible to create a hermetically sealed society based on a single ethical code over the long term," says Lavi. "ATA's fashion tells a story of modesty, austerity and a lack of fashion sense. Hans and Erich Moller didn't believe that it was their factory's job to keep up with current fashions. Their thinking was simple: You have to wear army uniforms, you need work clothing and leisure clothing - to go to the [kibbutz] dining room on Shabbat, so we'll give them good blue pants and a white shirt they can use for years. Women have to wear dresses, so we'll manufacture dresses, children need clothing so we'll make them from the remnants of the men's clothes. The women's clothing also began with remnants of men's clothing and dyed work or army clothes." Forced to be fashionable A turning point occurred immediately after the Six-Day War, when Israel began to become a part of the international fashion scene. The first boutiques opened in Tel Aviv along Dizengoff Street, and the khaki clothes and kova tembel lost their ultimate Israeli status. The image of the sabra in shorts and sandals was replaced by the Israeli who aspired to look like non-Israelis. ATA had to find its place in the bustling fashion industry, and to quickly introduce more modern clothing. The factory developed new products, including acrylic knits, raincoats, minidresses, plaid flannel shirts and bell-bottom Dacron pants. But it was a long story of trial and error, and the factory began to pile up losses. In 1962 Hans Moller died and the family ran into trouble running the factory. Amos Ben-Gurion, son of the founding prime minister, was appointed CEO, but the losses continued to mount. In 1964 the factory was sold to Tibor Rosenbaum, a Swiss businessman. With the ownership change, national spirit was pushed aside. ATA hired external fashion designers to design the collections. The first designer invited to design a collection for the factory, in 1965, was Lola Bar, who brought an image of elitist luxury. "Until the Six-Day War, Israel was closed to the outside world. Then suddenly television and magazines began to arrive, and we picked up trends much more quickly, and wanted to emulate other countries," says Lavi. "People began to become realistic about the socialist vision and everyone wanted to live well." The fashion designers who worked for ATA included Oded Gera, Shuki Levy and Jerry Melitz. Each designed three to five collections before being replaced by the next designer. The new direction aroused renewed interest in ATA products, but it wasn't enough to cover the losses. By that measure, the move was a failure. This may have been because each new ATA design went through so many manufacturing stages, it already looked outdated by the time it reached the store. "The factory did everything from spinning the thread to producing the clothing, so it was very difficult to keep up with the changing fashions," says Lavi. "The system was too complicated, inefficient and outdated." In 1978 ATA received the franchise to produce and sell Levi's jeans in Israel. At the time this looked promising, but in hindsight it apparently sealed the factory's fate. The transition from khaki to jeans heralded a basic change in Israeli society, which meant the end of the austerity era and a transition to free consumption and luxuries. But the ATA managers knew how to sell khaki. They didn't know how to sell jeans. ATA lost its unique place on the local scene, its ability to define the sabra look, and became just another clothing firm with no real advantage. Litvin says that this is evident in the advertisements for the factory, some of which will be displayed at the exhibition. "Until the mid-1960s there were very few ads; they simply didn't believe in it. They believed in making good clothes. Later one can see the American influence, which is evident in the ads." One of the most prominent ones, from 1968, presents two couples, man and wife. One couple is wearing the company's familiar 1948 clothes, and the second is in fashionable American cowboy outfits. "They're fashionable, they look like cowboys, but ATA is involved in this change, and that's the message," explains Litvin. No records of design ATA did not represent a uniform fashion, although it is largely identified with the "uniforms" of the early settlers. It represented the changes in Israelis' clothing, from the uniform of the new Israeli pioneer through khakis that suited the 1950s austerity and up until when Israel opened to outside influences. When the factory closed, the documents found there included plenty of internal correspondence, but not a single memo on the design of specific clothing items, say Lavi and Litvin. "The person in charge was Hans Moller, an industrialist who was interested in efficiency. He wanted the factory to operate properly, to sell high quality products. Fashion didn't interest him," says Lavi. ATA had no records of the design process, says Litvin. "We had trouble finding material indicating who was responsible for ATA's fashionable line, even in the 1960s and 1970s. There are no records of that. The only information is from the clothes, the ads and a few interviews with people." On the other hand, he says, "There's a lot of correspondence about business matters. Costs and materials. But not about fashion - there was no need to think about the next summer, what colors would be used, etc." Lavi continues: "We found patterns and fashion illustrations, but no correspondence with designers. We learned a lot about Hans Moller's concept of management. He wrote compulsively. He thought he could educate Israeli industry, the Israeli government, its stupid ministers - that's how he put it - teach people what proper management is and how industry and the country should be run. That passion can't be found in anything related to fashion." This also could describe the exhibition's curation. The wardrobe displayed in the exhibition shows no evidence of passion, thought or even particular interest, beyond excitement over the clothing's nostalgic value. Lavi says that she doesn't want to play up the exhibition's nostalgic side. "You don't tell the audience 'Come, look, there's nostalgia here,' but if you display something from the 1950s, 1960, 1970s, people can decide whether they want to feel nostalgic. I assume that because of the nostalgia nowadays, this aspect may be played up." "We weren't trying to discuss fashion, but to see the factory as an Israeli story," says Lavi. "Our motivation wasn't fashion. We display fashion, we show men's, women's and children's clothing in chronological order, write about them and explain them, so for anyone who wants to see a fashion exhibit, it's there. But it's not really a fashion exhibit." She stops for a moment and adds: "Maybe that's actually a good thing. Maybe it enables us to look at it without being too much in love with the thing itself." Israeli fashion refers to fashion design and modeling in Israel. Israel has become an international center of fashion and design.[1] Tel Aviv has been called the “next hot destination” for fashion.[2] Israeli designers, such as swimwear company Gottex, show their collections at leading fashion shows, including New York’s Bryant Park fashion show.[3] In 2011, Tel Aviv hosted its first Fashion Week since the 1980s, with Italian designer Roberto Cavalli as a guest of honor.[4]The ATA textile factory was founded in Kfar Ata in 1934 by Erich Moller, a Jewish industrialist from Czechoslovakia. ATA specialized in work clothes and uniforms, reflecting the Zionist and socialist ideology of the time.[5] Factory production spanned every aspect of garment-making, from thread manufacture to sewing and packaging.[6] The name of the factory was invented by Hebrew novelist S.Y. Agnon. ATA is an acronym for the Hebrew words "Arigei Totzeret Artzeinu" - "fabrics manufactured in our land."[7]In the early years of the state, Ruth Dayan, wife of Moshe Dayan, founded Maskit, a fashion and decorative arts house that helped to create jobs for new immigrants while preserving the Jewish ethnic crafts of various communities living in Israel.[8] In 1955, Dayan met fashion designer Finy Leitersdorf, who designed clothes and accessories for Maskit for 15 years. The two collaborated on a joint exhibit of Maskit designs at the Dizengoff Museum (today the Tel Aviv Museum).[8] Maskit produced textiles, clothing, objets d’art and jewelry.[9]In 1956, Lea Gottlieb founded Gottex, a high-fashion beachwear and swimwear company that became a leading exporter of designer bathing suits.[10]Israeli fashion has been worn by some of the world's most famous women, among them Jackie Kennedy, Princess Diana, Katharine Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor and Sarah Jessica Parker. ebay3345